Unfortunately, on September 19, 1808, the water on the street the theater was on was shut off to fix an issue with the system. The next morning, a fire started at around 4AM. With little means to effectively fight the blaze, it took just 3 hours to destroy the historic building and, along with more mundane things, a fair number of manuscripts that would today be given the always inaccurate moniker of “priceless”, as well as the late George Frideric Handel’s organ he had donated to the theater. On top of this, over 20 people lost their lives, and many dozens more were injured.

The loss of the theatre was a huge blow to the London community. You see, thanks to the Licensing Act of 1737, at the time, there were only two theaters in all of London that had been granted the right to perform full length spoken plays, and even these had to be approved before hand by government officials. All the other non-patent theaters, outside of occasionally temporary patents, were forced to restrict themselves to songs, acrobatics, dances, and the like. When they did show plays, they had to be mimed to stay within the bounds of the law.

Given the popularity of plays at the time and now with only one venue in town able to show them, efforts were quickly made to build a new theatre in place of the old, despite the lack of funds by the principal owners of the old structure to do so. You see, the insurance payout for the old building was only £50,000 (about £4 million or $5 million dollars today), with the cost to build a new theater to at least the level of the old estimated to be about three times that amount.

Stepping up to support the project, £10,000 was donated by the Duke of Northumberland. However, instead of accepting this, one of the principal owners of the theater and one of the most popular actors in all of Britain, John Kemble, refused the donation as such. Instead, he sent the Duke a bond promising to pay the sum back. The Duke, in turn, sent Kemble back his bond, along with a letter noting that as there was likely to be a bonfire to celebrate the start of construction, Kemble should throw his bond in it to “heighten the flames”.

A donation of £1,000 also came in from the Prince of Wales, future King George IV. The remaining funds comprising nearly £80,000 were acquired via subscription shares.

Money in hand, construction of the newer, improved Covent Garden Theatre began on January 2, 1809 under the supervision of famed architect Sir Robert Smirke, with the Prince of Wales himself ceremonially laying the first stone.

Things became even more urgent to get the theater built when, in February of 1809, the other theater in London allowed to show full plays, Drury Lane, burned to the ground.

Going back to Covent, nine months after the first stone was laid, a theater was born, largely superior to the original save for a few controversial changes. These included two galleries that were much smaller than the originals, meaning less seating for the plebeians. These also offered such a restricted view that patrons would come to complain that they could only see the legs of those on the stage.

Similarly, the third tier of the theatre (which had previously been freely available to the general public to purchase tickets for) had been converted into very large box seats areas to be rented by the year by wealthy patrons. These came complete with private areas where a curtain could be drawn, something quickly criticized for allegedly being so that the elite could solicit the services of prostitutes who often could be found at theaters of the age. In fact, many of the actresses themselves supplemented their income in this way, leading to the British expression “Said the actress to the Bishop”, implying illicit things actresses would tell ministers during confession. This was a precursor to the American version of an expression with the same meaning, “That’s what she said”, which was first popularized in the 1970s on Saturday Night Live.

Going back to the theater, in addition to these controversial changes, to help recoup the costs of rebuilding the new structure, Kemble raised the price of tickets about 15%, with the exception that the cost of the gallery, which as noted now had extremely restricted viewing, remained the same.

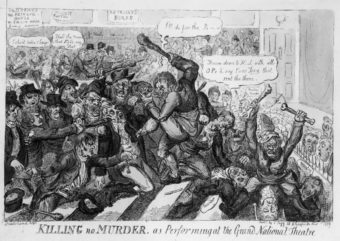

This brings us to opening night- September 18, 1809. Things started out innocently enough with the singing of the National Anthem, but then immediately turned tumultuous, with the crowd loudly chanting things like “Old prices!” throughout the performance of Macbeth.

Of course, actors and actresses of the age were used to this behavior from crowds. The idea of a “passive audience” is a fairly recent phenomenon, even in theatre. Throughout history crowds have always been encouraged in some way to express their enthusiasm, and even sometimes take part in the show, going all the way back to Ancient Greece where audience participation in plays and speeches was practically a civic duty.

The obvious downside of this is that crowds also felt entitled to express their displeasure in any way they pleased. As an example we have this 19th century account of a performance reported in the New York Times:

John Ritchie… made his debut before a Hempstead audience at Washington Hall a few evenings ago. He had a crowded house, and was warmly received, in fact, it was altogether too hot for him, there being distributed among the audience a bushel or two of rotten tomatoes. The first act opened with Mr. Ritchie trying to turn a somersault. He probably would have succeeded had not a great many tomatoes struck him, throwing him off his balance and demoralizing him. It was some time before the audience could induce him to go on with the performance. He next attempted to perform on the trapeze. As he lay upon the bar with his face toward the audience, a large tomato thrown from the gallery struck him square between the eyes, and he fell to the stage floor just as several bad eggs dropped upon his head. Then the tomatoes flew thick and fast, and Ritchie fled for the stage door. The door was locked, and he ran the gauntlet for the ticket office through a perfect shower of tomatoes. He reached it, and the show was over.

While you might think ruining the show in such a way would cause the better paying audience members to see to it that the plebs in the cheap seats would knock it off, nobody seemed to mind as half the fun of going to these shows was interacting with the performers in some way for some (particularly in the cheap seats) and for others observing what certain members of the crowd would get up to during the show. If a performance was good, the crowd would quickly see to it that anyone interfering in a negative way would be jeered down. If it was bad, well, the audience’s response was more fun to watch and take part in then. It was all about who could be more entertaining- the people on the stage, or the people in the crowd, or quite often a mixing of the two.

In this particular case, however, it wasn’t what was happening on the stage that was eliciting the negative response. In fact, that night’s performance featured Kemble’s sister, Sarah Siddons, who was almost universally considered the greatest tragedienne of the era.

Things got even worse at this inaugural performance when it was finally, mercifully over and the protesters refused to leave. This prompted Kemble to send for the police. The bobbies ended up inflaming the situation, with the seething crowd deciding to start rioting. Some arrests were made, but the crowd still refused to disperse until well into the am.

As to why the police were completely ineffective here, beyond it being difficult to control a large, angry crowd, there was apparently heated debate on whether or not the police actually could legally force a crowd who had paid to be there to disperse.

The next day, protesters once again filled the theatre, upping the ante by sneaking drums, whistles, frying pans, bells, and rattles into the performance, which they then used to completely drown out the actors on stage. On top of that, they reportedly broke out into what would be referred to as the “OP dance”, in which they more or less all stomped loudly on the benches in the pit in time as they chanted for old prices.

This type of behavior continued on during every performance until the 23rd when Kemble himself spoke to the mob during that evening’s performance, attempting to placate them by explaining: “That a committee of gentlemen had undertaken to examine the finances of the concern, and that until they were prepared with their report the theatre would be closed.”

Kemble thus closed the theatre for a few days while a report on the price change was compiled, examining whether the increase in price was justified or not. Of course, given the committee examining the issue was a subset of the shareholders in the theater, nobody paid attention to the report when it came out showing that, indeed, the approximately 15% price increase was deemed reasonable by said shareholders.

The crowd thus continued their antics when the theater opened back up, with newspapers as far as Edinburgh regularly reporting on the nightly tumult at the Covent Garden Theater. People across the nation quickly took sides, with those wanting the prices reversed referring to themselves as “OPs”, and those who were on the side of the theater owners called “NPs”.

Beyond making a ruckus at the shows, protesters also reportedly regularly gathered outside of Kemble’s home at all hours chanting for “original prices”, including coming up with a variety of unflattering songs illustrating what they thought of Kemble and his new prices.

Back in the theater, along with plastering it in banners and posters protesting the price change, the theater denizens began to sneak even more ridiculous things into performances including farm animals, flocks of pigeons they’d release inside the building, giant distracting hats and even a coffin with a banner stating in part “Here lies the body of the new price…”

Protesters additionally began turning up to performances in outlandish costumes including full drag, as well as organizing races and mock fights in the pit- in all cases, attempting to either drown out anything the actors were doing on stage or otherwise distract from it.

Kemble got so desperate to try to stop the teeming masses ruining the shows that he even went as far as paying professional boxers, including former boxing champion Daniel Mendoza (the guy who popularised that weird way all old-timey boxers seem to stand) to act as bouncers to enforce law and order.

Similar to the police, Mendoza and his fellow fighter’s presence unsurprisingly failed to calm the crowd down and caused even more tumult to erupt during performances anytime the fighters tried to intervene.

While you might think surely at some point people would get tired of the whole thing and want to just settle down and watch the performance they paid the inflated prices to see- the OPs refused to quit night after night.

And so it was that with no end in site, after about three months of near constant unrest at the shows, the former extremely popular actor, Kemble, gave in to the demands, issuing a public apology to the gathered crowd at the theatre on December 15th as well as formally restoring the old prices. Kemble also dropped all charges that had been leveled at protesters that had been arrested in the interim.

Now having the 19th century version of TV back, the masses were satiated. This was much to the relief of the royals, some of whom feared the OPs might band together against other similar perceived slights against commoners at the time as newspapers were more and more drawing parallels between what was happening at that theater with other aspects of life in the British empire. But now with their entertainment back, no such revolution occurred.

Things worked out for the theater as well, even at the original prices, with ticket sales for the following decade averaging around £80,000 per year, about double the annual operating costs.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Who Invented the Sporting Wave?

- The United States v. Paramount and How Movie Theater Concessions Got So Expensive

- The Truth About Gladiators and the Thumbs Up

- Has There Ever Been an Actual Case of Someone Being Pelted With Tomatoes During a Performance?

Bonus Fact:

If you happen to be wondering how we went from a couple thousand years of audience participation in performances to the passive audiences we have today in the span of only about a century, to begin with, shows started shifting from the actors actively acknowledging the audience was there, generally purposefully interacting with them, to instead pretending the audience was non-existent and performing as though what was happening on the stage was real and sort of “in another dimension”, so to speak. Essentially, the invisible fourth wall was created to preserve the illusion, and audiences began to more and more be expected not to break that wall down by interrupting the performance.

Other factors that helped this switch along included advancements in stage lighting, allowing for shifting the focus from both the audience and the stage to just the stage, further solidifying the invisible “fourth wall”. Accordingly, theatres were redesigned and rather than having the classic horseshoe shape (so wealthy spectators in the seats high up could enjoy the audience’s show as much as what was happening on the stage, as well as easily observe what other wealthy patrons were getting up to), now every seat commonly faced towards the stage and it became difficult to see what members of the audience were doing. Effectively, the audience ceased to be part of the night’s entertainment.

As the show began to focus more on what was happening on the stage, the cheap seats in the pit began to be upgraded from simple wooden benches to plush seats where the wealthy began to sit so they could see the performers better. When this happened, those wealthy patrons sitting near the stage were less than enthusiastic about getting hit by poorly aimed projectiles, helping to morph the rules to this being no longer accepted behavior in the theatre, though it has persist somewhat in certain other venues.

For instance, throwing things on the stage at pop music concerts is relatively common, and even the Beatles once lamented that for a little over a year period they were continually hit on stage, first with soft Jelly Babies in England and then in America with the much harder Jelly Beans. In fact, the Beatles’ 1964 performance in San Francisco had to be completely stopped twice due to the barrage of Jelly Beans becoming too intense, forcing them to retreat and implore the audience to knock it off.

Beyond this, heckling at comedy shows is still relatively common. Perhaps the best example of all where non-passive audiences have endured is at most sporting events, where boisterous behavior of patrons still often resembles that of audiences through most of history. But due to stricter rules and that the rowdier members of the crowd are typically further from the field of play, this doesn’t usually disrupt the sporting spectacle, though the athletes still have to endure non-stop taunting or cheering (and the occasional projectile) in many professional sports from fans at all levels.

Of course, it is not uncommon to have an (often inebriated) fan running onto the field of play and being chased around by security. Despite this interrupting the show, the rest of the audience paid to see, everyone tends to cheer for the runner and find the whole thing thoroughly enjoyable, particularly the longer the fan on the field can manage to evade capture… We really haven’t changed that much at all, it turns out.

Expand for References- The OP War, Libertarian Communication and Graphic Reportage in Georgian London

- This is the House that Jack Built

- The Covent Garden Old Price Riots: Protest and Justice in Late‑Georgian London

- British Sporting Literature and Culture in the Long Eighteenth Century

- Covent Garden Theatre 1808 fire and rebuild

- 19th-Century Theatre

- Covent Garden Theatre – The houses twain

- The Old Price Riots of 1809: theatre, class and popular protest

- Theatrical Riots and Cultural Politics in Eighteenth-Century London

- Royal Opera House

- Old Price Riots

- Theaters Act 1843

- Is There Any Documented Case of Someone Being Pelted by Tomatoes?

- The Curious Case of the Claque

- John Philip Kemble

- Why Do Old Timey Boxers Pose for Photos That Way

The post That Time the British Rioted for Three Months Over the Cost of Theater Tickets appeared first on Today I Found Out.

from Today I Found Out

by Karl Smallwood - September 27, 2019 at 11:41PM

Article provided by the producers of one of our Favorite YouTube Channels!

-

No comments:

Post a Comment