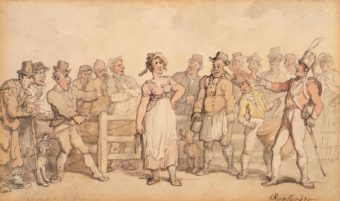

Perhaps not coincidentally around the same time these impotence trials were going on throughout parts of Europe, a rather different means of divorcing one’s spouse popped up in Britain- putting a halter around your wife, leading her like an animal to a local market, loudly extolling her virtues as you would a farm animal, including occasionally listing her weight, and then opening up bidding for anyone who wanted to buy her. On top of this, it wasn’t uncommon for children to be thrown in as a package deal…

While you might think surely something like this must have only occurred in the extremely distant past, this is actually a practice that continued into the early 20th century. So how did this all start and why was it seen as an perfectly legal way for a couple to divorce?

Well, it turns out that nobody is exactly sure how the practice of auctioning a wife got started. There is a mention of it going back all the way to at least 1302 where an individual deeded his wife to another man, but the next known instances didn’t start popping up until the late 17th century, with one of the earliest occurring in 1692 when one John Whitehouse sold his wife to a “Mr. Bracegirdle”.

However, noteworthy here was that four years later, when a man by the name of George Fuller sold his wife to Thomas Heath Maultster, Thomas was nonetheless later fined and ordered to perform a penance for living with his purchased wife. This was despite that all parties involved were in agreement over the sale, seemingly indicating this practice was not yet widely accepted at this point as it would come to be.

On that note, the rise in popularity of this method of divorce came about after the passage of the Marriage Act of 1753 which, among other things, required a clergyman to perform a marriage to make it legally binding. Before that, while that certainly was a common option, in Britain two people could also just agree that they were married and then they were, without registering that fact officially. Thus, without an official registration anywhere, it was also easier to more or less undo the act and hitch up with someone else without officials being any the wiser if neither the husband nor wife complained about the separation to authorities.

As a fun brief aside, the fact that members of the clergy and other officials at this point were often unaware of things like the current marital status of two people is more or less how the whole “If anyone can show just cause why this couple cannot lawfully be joined together in matrimony, let them speak now or forever hold their peace,” thing started. Not at this point a meaningless part of the marriage ceremony, at the time the minister was really asking if anyone knew, for instance, if one or both of the couple he was marrying might already be married or there might be any other legal reason why he shouldn’t marry the couple. For more on all this, see our article: What Happens When Someone DOES Object During a Wedding and Where Did This Practice Come From?

In any event, after the passage of the Marriage Act of 1753 and up to about the mid-19th century, selling your wife at auction seems to have become more and more popular among commoners particularly, who otherwise had no practical means of legally separating. The funny thing about all this is, however, that it wasn’t actually a legal way to get a divorce. But as the commoners seemed to have widely believed it was, clergy and government officials for a time mostly turned a blind eye to the whole thing, with some exceptions.

Illustrating both sides of this, in 1818 an Ashbourne, Derby magistrate sent the police out to break up a wife auction. This was documented by one Rene Martin Pillett who witnessed the event and subsequently wrote about it in his book, Views of England. In it, he states:

In regard to the sale at Ashburn, I will remark that the magistrate, being informed that it would take place, wished to prevent it. Constables were dispatched to drive off the seller, purchaser, and the woman for sale, when they should make their appearance in the market place to perform the ceremony, but the populace covered the constables with mud, and dispersed them with stones. I was acquainted with the magistrate, and I desired to obtain some information in regard to the opposition he had endeavored to make to the performance of the ceremony, and the right which he assumed at that conjuncture. I could obtain no other than this: “Although the real object of my sending the constables, was to prevent the scandalous sale, the apparent motive was that of keeping the peace, which people coming to the market in a sort of tumult, would have a tendency to disturb. As to the act of selling itself, I do not think I have a right to prevent it, or even to oppose any obstacle to it, because it rests upon a custom preserved by the people, of which perhaps it would be dangerous to deprive them by any law for that purpose.”

Pillett goes on, “I shall not undertake to determine. I shall only observe that this infamous custom has been kept up without interruption, that it is continually practised; that if any county magistrates, being informed of a proposed sale, have tried to interrupt it, by sending constables, or other officers to the place of sale, the populace have always dispersed them, and maintained what they consider their right, in the same manner as I have seen it done at Ashburn.”

That said, the press, in general, seemed to have almost universally condemned the practice from the way they talked about it. For example, as noted in a July of 1797 edition of The Times: “On Friday a butcher exposed his wife to Sale in Smithfield Market, near the Ram Inn, with a halter about her neck, and one about her waist, which tied her to a railing, when a hog-driver was the happy purchaser, who gave the husband three guineas and a crown for his departed rib. Pity it is, there is no stop put to such depraved conduct in the lower order of people.”

Nevertheless, particularly in an age when marriage was often more about practical matters than actually putting together two people for the purposes of being happy with one another, there were a lot of unhappy couples around and if both people agreed they’d be better off splitting, a means was needed to do so. The British commoners, having almost no other feasible way to do this, simply got inventive about it.

This might all have you wondering what rationale was used to justify this exact method of divorcing and why people just didn’t split and forget about what authorities thought. As to the latter question, people did do that in droves, but there was legal risk to it to all involved.

You see, at this point a wife was in a lot of ways more or less considered property of her husband. As noted by judge Sir William Blackstonein in 1753, “the very being… of the woman, is suspended during the marriage, or at least is consolidated and incorporated into that of her husband…”

In turn, the husband was also expected to do his part to take care of his wife no matter what and was responsible for any debts she incurred, etc. Just as importantly, while a man having a mistress wasn’t really that uncommon, should a wife find her own action on the side, perhaps with someone she actually liked, this was by societal standards of the day completely unacceptable. This didn’t stop women from doing this, of course, even occasionally leaving their husbands completely and living with a new man. But this also opened up a problem for the new man in that he had, in effect, just stolen another man’s property.

Thus, the dual problem existed that the husband still was legally obligated to be responsible for any debts his wife incurred and to maintain her. He could also be prosecuted for neglecting his duty there, whether his wife had shacked up with another man or not. As for the new suitor, he could at any point also be subjected to criminal proceedings, including potentially having to pay a large fine to the husband for, in essence, stealing his property, as well as potential jail time and the like.

Thus, the commoners of England decided leading a wife as if she was cattle to the market and auctioning her off was a legal way to get around these problems. After all, if the wife was more or less property, why couldn’t a husband sell her and his obligations to her in the same way he sold a pig at market?

While you might think no woman would ever agree to this, in most of the several hundred documented cases, the wife seemingly went along happily with the whole thing. You see, according to the tradition, while the wife technically had no choice about being auctioned off in this way, she did have the right to refuse to be sold should the winning bidder not be to her liking, at which point the auction seems to have continued until a suitable buyer was found. For example, in one case in Manchester in 1824, it was reported that, “after several biddings she [the wife] was knocked down for 5s; but not liking the purchaser, she was put up again for 3s and a quart of ale.”

Further, there are a few known instances of the wife buying herself, such as in 1822 in Plymouth where a woman paid £3 for herself, though in this instance apparently she had a man she’d been having an affair with that was supposed to purchase her, but he didn’t show up… Ouch…

On that note, it turns out in most of the documented instances, the buyer was also usually chosen long before the actual auction took place, generally the woman’s lover or otherwise the man she wanted to be with more than her former husband. And, as she had the right to refuse to be sold, there was little point in anyone else bidding. In fact, accounts exist of the after party sometimes seeing the husband who sold the wife taking the new couple out for drinks to celebrate.

Owing to many involved in such divorces being poor and the suitor often being chosen before hand, the price was usually quite low, generally under 5 shillings, even in some reported cases a mere penny- just a symbolic sum to make the whole thing seem more official. For example, as reported in February 18, 1814,

A postillion, named Samuel Wallis, led his wife to the market place, having tied a halter around her neck, and fastened her to the posts which are used for that purpose for cattle. She was then offered by him at public auction. Another postillion, according to a previous agreement between them, presented himself, and bought the wife thus exposed for sale, for a gallon of beer and a shilling, in presence of a large number of spectators. The seller had been married six months to this woman, who is only nineteen years old.

Not always cheap, however, sometimes honor had to be served when the more affluent were involved. For example, in July of 1815 a whopping 50 guineas and a horse (one of the highest prices we could personally find any wife went for), was paid for a wife in Smithfield. In her case, she was not brought to market via a halter either, like the less affluent, instead arriving by coach. It was then reported that after the transaction was complete, “the lady, with her new lord and master, mounted a handsome curricle which was in waiting for them, and drove off, seemingly nothing loath to go.”

After dinner there was a stir and a bustle in the Inn Yard. The explanation came that “A man is going to sell his wife and they are leading her up the yard with a halter round her neck”. “We will go and see the sale,” said the Duke.

On entering the yard, however, he was so smitten with the woman’s beauty and the patient way she waited to be set free from her ill‑conditioned husband, the Inn’s ostler, that he bought her himself.

He did not, however, initially take her as his wife, as his own wife was still alive at the time. However, he did have the woman, former chambermaid Anne Wells, educated and took her as his mistress. When both his own wife and Anne’s former husband died within a few years of each other not long after, he married Anne himself in 1744. Their marriage was apparently a happy one until her own death in 1759. An 1832 edition of the The Gentleman’s Magazine concludes the story:

On her death-bed, she had her whole household assembled, told them her history, and drew from it a touching moral of reliance on Providence; as from the most wretched situation, she had been suddenly raised to one of the greatest prosperity…

Not always a completely happy ordeal, however, there are known cases where the sale followed a husband finding out his wife was cheating on him, and then the man she was having an affair with simply offering to buy her to avoid the whole thing becoming extremely unpleasant for all involved or needing to involve the courts.

It has been suggested this may be why elements of the spectacle were rather humiliating to the women. Perhaps early on when the tradition was being set some husbands who had wives that had been cheating on them or otherwise just making their lives miserable took the opportunity to get a last jab at her before parting ways.

Not always just humiliating via being treated as an animal in front of the whole town, sometimes verbal insults were added. For example, consider the case of Joseph Tomson. It was reported his little sales pitch for her was as follows:

Gentlemen, I have to offer to your notice my wife, Mary Anne Thomson, otherwise Williams, whom I mean to sell to the highest and fairest bidder. Gentlemen it is her wish as well as mine to part for ever. She has been to me only a born serpent. I took her for my comfort, and the good of my home; but she became my tormentor, a domestic curse, a night invasion, and a fairly devil. Gentlemen, I speak truth from my heart when I say may God deliver us from troublesome wives and frolicsome women! Avoid them as you would a mad dog, a roaring lion, a loaded pistol, cholera morbus, Mount Etna or any other pestilential thing in nature. Now I have shewn you the dark side of my wife, and told you her faults and failings, I will introduce the bright and sunny side of her, and explain her qualifications and goodness. She can read novels and milk cows; she can laugh and weep with the same ease that you could take a glass of ale when thirsty. Indeed gentlemen she reminds me of what the poet says of women in general: “Heaven gave to women the peculiar grace, To laugh, to weep, to cheat the human race.” She can make butter and scold the maid; she can sing Moore’s melodies, and plait her frills and caps; she cannot make rum, gin, or whisky, but she is a good judge of the quality from long experience in tasting them. I therefore offer her with all her perfections and imperfections, for the sum of fifty shillings.

Not exactly an effective sales pitch, nobody bid for about an hour, which perhaps was further humiliating motivation for such a pitch. Whatever the case, he then dropped the price and eventually got 20 shillings and a dog from one Henry Mears. Apparently Mears and his new wife parted in, to quote, “perfect good temper” as did Thomson.

All this said, while many known accounts seem to be of people where both the husband and wife were in agreement about the separation and use of the auction as the method of divorce, this wasn’t always the case on both sides. For instance, we have the 1830 case in Wenlock Market where it was reported that the woman’s husband “turned shy, and tried to get out of the business, but Mattie mad’ un stick to it. ‘Er flipt her apern in ‘er gude man’s face, and said, ‘Let be yer rogue. I wull be sold. I wants a change’.” She was subsequently sold for 2 shillings and 2d.

In another case, one drunk individual in 1766 in Southwark decided to sell his wife, only to regret the decision later and when his wife wouldn’t come back to him, he killed himself… In a bit more of a happy ending type story, in 1790 a man from Ninfield was at an inn when he decided to sell his wife for a half a pint of gin. However, he would later regret the loss, so paid some undisclosed price to reacquire her, an arrangement she would have had to agree to for it to be completed.

On the other side, there do seem to be some cases where the woman was seemingly auctioned against her will. However, for whatever it’s worth, again, in these cases by tradition she did always have the option to refuse a sale, though of course not exactly a great option in some cases if it meant going back to a husband who was eager to be rid of her. Nonetheless, this may in part explain why there are so few known accounts of women not seeming to be happy about the whole thing. While it might be going to an uncertain future if a man hadn’t already been prearranged, at least it was going to someone who actually wanted her, and willing to outbid other bachelor’s around town (in these cases being a legitimate auction).

Going back to the legality of it all, at least in the minds of the general public, it would seem people considered it important that the whole thing needed to be extremely public, sometimes even announcing it in a local paper and/or having a town crier employed to walk through town announcing the auction and later sale. This made sure everyone around knew that the husband in question was no longer responsible for his wife, nor her debts or other obligations, and announced that the husband had also agreed to dissolve any former rights he had to his wife, ensuring, again at least in the minds of the general public, that the new suitor could not be criminal prosecuted for taking the wife of another man.

For further legal protection, at least in their minds, some would even go so far as to have a contract drawn up, such as this one from Oct. 24, 1766:

It is this day agreed on between John Parsons, of the parish of Midsummer Norton, in the county of Somerset, clothworker, and John Tooker, of the same place, gentleman, that the said John Parsons, for and in consideration of the sum of six pounds and six shillings in hand paid to the said John Parsons, doth sell, assign, and set over unto the said John Tooker, Ann Parsons, wife of the said John Parsons; with all right, property, claim, services, and demands whatsoever, that he, the said John Parsons, shall have in or to the said Ann Parsons, for and during the term of the natural life of her, the said Ann Parsons. In witness whereof I, the said John Parsons, have set my hand the day and year first above written.

JOHN PARSONS.‘Witness: WILLIAM CHIVERS.’

While none of this was legally binding in the slightest, for whatever it’s worth, there is at least one case where a representative of the state, a Poor Law Commissioner, actually forced a sale of a wife. In this case, they forced one Henry Cook to sell his wife and child to avoid the Effingham workhouse having to also take in his family. The woman was ultimately sold for a shilling. The parish did, at the least, pay for a wedding dinner after the fact… So only 99.9% heartless in kicking a man while he was down. For much more on the nightmare that was workhouses, do go check out our absolute favorite BrainFood Show podcast episode we’ve ever done- The Sledgehammer for the Poor Man’s Child.

In any event, there were also known court cases where the courts upheld such a divorce, though seemingly always jury trials. For example, in 1784 a husband tried to claim his former wife as his own again, only to have a jury side with the new couple, despite that there was literally no law on the books that supported this position.

On the flipside there were many more cases where the courts went the other way, such as the case of an 1835 woman who was auctioned off by her husband and sold for fifteen pounds, with the amount of the transaction indicating this person was likely reasonably well off. However, upon the death of her former husband, she went ahead and claimed a portion of his estate as his wife. The courts agreed, despite the objections of his family who pointed out the previous auction and that she had taken up a new husband.

Now, as you can imagine, literally leading your wife by a halter around her neck, waist, or arm to market and putting her up on an auction block, even if seemingly generally a mutually desired thing, from the outside looking in seemed incredibly uncivilized and brutish. As such, foreign entities, particularly in France, frequently mocked their hated neighbors in England for this practice.

From this, and the general distaste for the whole thing among the more affluent even in Britain, the practice of auctioning wives off began to be something the authorities did start to crack down on starting around the mid-19th century. As noted by a Justice of the Peace in 1869, “publicly selling or buying a wife is clearly an indictable offence … And many prosecutions against husbands for selling, and others for buying, have recently been sustained, and imprisonment for six months inflicted…”

In another example, in 1844 a man who had auctioned off his former wife was being tried for getting married again as he was, in the eyes of the state, still considered to be married to his original wife. The seemingly extremely sympathetic judge, Sir William Henry Maule, admonished him for this fact, while also very clearly outlining why many of the less affluent were forced to use this method for divorce, even in cases where the wife had left and taken up with another man:

I will tell you what you ought to have done; … You ought to have instructed your attorney to bring an action against the seducer of your wife for criminal conversation. That would have cost you about a hundred pounds. When you had obtained judgment for (though not necessarily actually recovered) substantial damages against him, you should have instructed your proctor to sue in the Ecclesiastical courts for a divorce a mensa et thoro. That would have cost you two hundred or three hundred pounds more. When you had obtained a divorce a mensa et thoro, you should have appeared by counsel before the House of Lords in order to obtain a private Act of Parliament for a divorce a vinculo matrimonii which would have rendered you free and legally competent to marry the person whom you have taken on yourself to marry with no such sanction. The Bill might possibly have been opposed in all its stages in both Houses of Parliament, and together you would have had to spend about a thousand or twelve hundred pounds. You will probably tell me that you have never had a thousand farthings of your own in the world; but, prisoner, that makes no difference. Sitting here as an English Judge, it is my duty to tell you that this is not a country in which there is one law for the rich and one for the poor. You will be imprisoned for one day. Since you have been in custody since the commencement of the Assizes you are free to leave.

In the end, thanks to the masses having to resort to such extreme measures as simply abandoning a spouse and never legally separating, auctioning the wife off as if she was an animal, and the aforementioned impotence trials, divorce law was eventually revamped in Britain with the passage of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857, finally allowing at least some affordable means of divorce for commoners, particularly in cases of abandonment or adultery. This, combined with the courts cracking down on wife auctions, saw the practice more or less completely die off by the end of the 19th century, though there were a few more known cases that continued in Britain all the way up to 1926 where one Horace Clayton bought a woman he then called his wife for £10 from her previous husband.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Can You Really Just Go Online and Order a Wife from Some Other Country?

- That Time Women Could Divorce Their Husbands By Having Intercourse in Court

- What Happens When Someone DOES Object During a Wedding and Where Did This Practice Come From?

- Can Sea Captains Really Officiate Legally Binding Marriages?

- Jus Primae Noctis: Fact or Fiction?

Bonus Facts:

In case anyone’s wondering, while there are only a handful of known cases of it happening, there were a few husbands sold as well, though as part of the point of the whole thing was for the husband to publicly declare he was no longer obligated to his wife and for the woman in question to agree to be wed to another man, with rights to her transferring to him, the auction of a husband didn’t really make a lot of sense from a practical standpoint. Nevertheless, it did happen. For example, consider this case reported a March 18, 1814 edition of the Statesmen:

On Saturday evening an affair of rather an extraordinary nature was brought before his Lordship the Mayor of Drogheda. One Margaret Collins presented a complaint against her husband, who had left her to live with another woman. In his defense, the husband declared that his wife was of a very violent disposition, which her conduct before the magistrate fully proved; that in her anger she had offered to sell him for two pence to her in whose keeping he then was; that she had sold and delivered him for three halfpence; that on payment of the sum, he had been led off by the purchaser; that several times, his wife, the seller, in her fits of anger had cruelly bitten him; that he still bore terrible marks of it (which he showed) although it was several months since he belonged to her. The woman who purchased, having been sent for to give her evidence, corroborated every fact, confirmed the bargain, and declared that she every day grew more and more satisfied with the acquisition; that she did not believe there was any law which could command him to separate from her, because the right of a wife to sell a husband with whom she was dissatisfied, to another woman who was willing to take up with him ought to be equal to the husband’s right, whose power of selling was acknowledged, especially when there was a mutual agreement, as in the present instance. This plea, full of good sense and justice, so exasperated the plaintiff, that, without paying any regard to his lordship, she flew at the faces of her antagonists, and would have mangled them with her teeth and nails, if they had not been separated…

It’s also worth noting that at least some English settlers to America carried on the tradition there, such as this account reported in the Boston Evening-Post on March 15, 1736:

Expand for ReferencesThe beginning of last Week a pretty odd and uncommon Adventure happened in this Town, between 2 Men about a certain woman, each one claiming her as his Wife, but so it was, that one of them had actually disposed of his Right in her to the other for Fifteen Shillings this Currency, who had only paid ten of it in part, and refus’d to pay the other Five, inclining rather to quit the Woman and lose his Earnest; but two Gentlemen happening to be present, who were Friends to Peace, charitably gave him half a Crown a piece, to enable him to fulfill his Agreement, which the Creditor readily took, and gave the Woman a modest Salute, wishing her well, and his Brother Sterling much Joy of his Bargain.

- Wife Selling

- Sale of a Wife

- Studies in the History of Jurisprudence

- Marriage Act of 1753

- Customs in Common: Studies in Traditional Popular Culture

- Road to Divorce

- Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857

- A Brief History of Wife Selling

- 19th Century Wife Selling

- Wife Sales

- Wife Selling

- The Long Struggle of Wives Under English Law

- Views of England

- Colonial Dames and Good Wives

- Chandos

The post That Surprisingly Recent Time British Husbands Sold Their Wives at Market appeared first on Today I Found Out.

from Today I Found Out

by Daven Hiskey - June 30, 2019 at 02:37AM

Article provided by the producers of one of our Favorite YouTube Channels!

-

No comments:

Post a Comment