Known as Project Horizon, the impetus for the plan came when the Soviets set their sites on the moon. As noted in the Project Horizon report, “The Soviet Union in propaganda broadcasts has announced the 50th anniversary of the present government (1967) will be celebrated by Soviet citizens on the moon.”

U.S. National Space policy intelligence thought this was a little optimistic, but still felt that the Soviets could probably do it by 1968. Military brass deemed this a potential disaster for the United States for several reasons.

To begin with, if the Soviets got to the moon first, they could potentially build their own military base there which they could use for a variety of secret projects safely away from the United States’ prying eyes. In the extreme, they could potentially launch nuclear attacks on the U.S. with impunity from that base.

Naturally, a military installation completely out of reach of your enemies both terrified and tantalized military officials.

Next up, if the Soviets landed on the moon first, they could try to claim the entire moon for themselves. If they did that, any move by the U.S. to reach the moon could potentially be considered an aggressive act, effectively making the moon off limits to the United States unless willing to risk war back home.

This was deemed to be a potential disaster as the moon, with its low gravity, was seen as a needed hub for launching deep space missions, as well as a better position to map and observe space from than Earth.

Beyond the practical, this would also see the Soviets not just claiming the international prestige of an accomplishment like landing and building a facility on the moon, but also countless other discoveries and advancements after, as they used the moon for scientific discovery and to more easily launch missions beyond.

Of course, the Soviets might do none of these things and allow the U.S. to use the moon as they pleased. But this wasn’t a guarantee. As noted in the Project Horizon report, “Clearly the US would not be in a position to exercise an option between peaceful and military applications unless we are first. In short, the establishment of the initial lunar outpost is the first definitive step in exercising our options.”

The threat of having the moon be in Soviet hands simply would not stand. As Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson would famously state in 1964, “I do not believe that this generation of Americans is willing to resign itself to going to bed each night by the light of a Communist moon.”

Thus, long before Kennedy would make his famous May 25, 1961 declaration before Congress that the U.S. “should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth”, military brass in the U.S. were dead-set on not just man stepping foot on the moon, but building a military installation there and sticking around permanently.

And so it was that in March of 1959, Chief of Army Ordnance Major General John Hinrichs was tasked by Chief of Research and Development Lieutenant General Arthur G Trudeau with developing a detailed plan on what was needed to make such a moon base happen. A strict guideline of the plan was that it had to be realistic and, towards that end, the core elements of the plan had to use components and equipment either already developed or close to being completed.

To facilitate the outline for the project, Major General John B. Medaris stated, “We grabbed every specialist we could get our hands on in the Army.”

The resulting report published on June 9, 1959 went into an incredible amount of detail, right down to how the carbon dioxide would be scrubbed from the air at the base.

So what did they come up with?

To begin with, it was deemed the transport side could be accomplished using nothing more than Saturn 1 and Saturn 2 rockets. Specifically, 61 Saturn 1s and 88 Saturn 2s would transport around a total of 490,000 lbs of cargo to the moon. An alternative plan was to use these rockets to launch much of the cargo to a space station in high Earth orbit. These larger sections would then be ferried over to the moon using a dedicated ship that would go back and forth from the Earth to the moon.

The potential advantage here was that for the Saturn rockets to get equipment to the moon, they were limited to about 6000 pounds per trip on average. But if only transporting something to orbit, they could do much greater payloads, meaning fewer rockets needed. The problem, of course, was that this version of the plan required the development of a ferrying rocket and an orbiting space station, which made it the less desirable option. Again, a strict guideline for the project was that the core of the plan had to use existing or near existing equipment and technology in order to expedite the project and get to the moon before the Soviets.

Whichever method was used, once everything was on the moon, a pair of astronauts would be sent to inspect everything and figure out if anything needed replaced. The duration of this first moon landing by man was slated to be a 1-3 month stay.

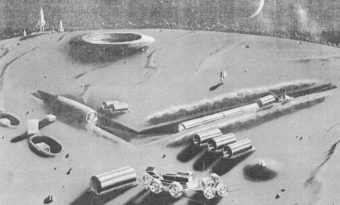

Next up, whatever replacement items that needed to be sent would be delivered, and then once all that was set, a construction crew would be sent to complete the base. The general plan there was to use explosives and a specially designed space bulldozer/backhoe to create trenches to put the pre-built units into. Once in place, they would simply be attached together and buried in order to provide added protection from meteorites and potential attacks, among other benefits.

As for the features of this base, this included redundant nuclear reactors for power, as well as the potential to augment this with solar power for further redundancy. Various scientific laboratories would also be included, as well as a recreation room, hospital unit, housing quarters, and a section made for growing food in a sustainable way. This food would augment frozen and dehydrated foods supplied from Earth.

The base would also have extensive radio equipment to facilitate the moon functioning as a communications hub for the U.S. military back on Earth that could not be touched by any nation on Earth at the time. On a similar note, it would also function as a relay for deep space communications to and from Earth.

Beyond the core base itself, a moon truck capable of transporting the astronauts and equipment around was proposed, as well as placing bomb shelters all around the base for astronauts to hide in if needed. Water, oxygen, and hydrogen would ultimately be provided from the ice on the moon itself, not only sustaining the astronauts but potentially providing any needed fuel for rockets, again to help facilitate missions beyond the moon and transport back home to Earth.

Of course, being a military installation, it was deemed necessary for the 12 astronauts that were to be stationed at the base at all times to be able to defend themselves against attack. Thus, for their personal sidearms, a general design for a space-gun was presented, more or less being a sort of shotgun modified to work in space and be held and fired by someone in a bulky suit.

The astronauts would also be given many Claymore like devices to be stationed around the base’s perimeter or where deemed needed. These could be fired remotely and more or less just sent a hail of buckshot at high speed wherever they were pointed.

Thanks to the lesser gravity and lack of tangible atmosphere, both of these weapons would have incredible range, if perhaps not the most accurate things in the world.

But who needs accuracy when you have nuclear weapons? Yes, the astronauts would be equipped with those too, including the then under development Davey Crockett nuclear gun. Granted, thanks to the lack of atmosphere, the weapon wouldn’t be nearly as destructive as it would be on Earth, but the ionizing radiation kill zone was still around 300-500 meters.

Another huge advantage of the Davey Crockett on the moon was that the range was much greater, reducing the risk to the people firing it, and the whole contraption would only weigh a little over 30-40 pounds thanks to the moon’s lesser gravity, making it easier for the astronauts to cart around than on Earth.

Of course, being a space base, Project Horizon creators naturally included a death ray in its design. This was to be a weapon designed to focus a huge amount of sun rays and ionizing radiation onto approaching enemy targets. Alternatively, another death ray concept was to build a device that would shoot ionizing radiation at enemy soldiers or ships.

As for space suits, according to the Project Creators, despite being several years before the character would make his debut in the comics, they decided an Iron Man like suit was the way to go, rather than fabric based as NASA would choose. To quote the report,

For sustained operation on the lunar surface a body conformation suit having a substantial outer metal surface is considered a necessity for several reasons: (1) uncertainty that fabrics and elastomers can sustain sufficient pressure differential without unacceptable leakage; (2) meteoroid protection; (3) provides a highly reflective surface; (4) durability against abrasive lunar surface; (5) cleansing and sterilization… It should be borne in mind that while movement and dexterity are severe problems in suit design, the earth weight of the suit can be allowed to be relatively substantial. For example, if a man and his lunar suit weigh 300 pounds on earth, they will only weigh 50 pounds on the moon.

Along with death rays, nuclear guns, and badass space suits, no self respecting moon base could be governed by anything as quaint as a simply named committee or the like. No, Project Horizon also proposed creating a “Unified Space Command” to manage all facets of the base and its operation, along with further exploration in space, including potentially a fleet of space ships needed to achieve whatever objectives were deemed appropriate once the base was established.

As to the cost of this whole project, the report stated,

The total cost of the eight and one-half year program presented in this study is estimated to be six billion dollars (*about $53 billion in 2019 dollars*). This is an average of approximately $700 million per year. These figured are a valid appraisal, and, while preliminary, they represent the best estimates of experienced, non-commercial, agencies of the government. Substantial funding is undeniably required for the establishment of a U. S. lunar outpost; however, the implications of the future importance of such an operation should be compared to the fact that the average annual funding required for Project HORIZON would be less than two percent of the current annual defense budget.

Of course, the reality is that the entire Apollo program ended up costing a little over $25 billion, so this $6 billion estimate likely would have ballooned to much greater levels had the base actually been built. That said, even massively more expensive, given the number of years, this would have still represented a relatively small portion of the United States’ annual defense budget, as noted.

Sadly, considering the initial plan was explicitly to make this a peaceful installation unless war broke out, meant mostly for scientific discovery, and considering what such a moon base would have meant for the direction of future space exploration, neither President Dwight D. Eisenhower, nor the American public had much interest in even going to the moon at all, let alone building a base there.

Yes, contrary to popular belief, the Greatest Generation was pretty non-enthusiastic about the whole space thing. In fact, even after Kennedy would make his famous speech before Congress and then at Rice University, a Gallup poll showed almost two-thirds of Americans were against the plan to land a man on the moon, generally seeing it as a waste of taxpayer dollars. Sentiments did not greatly improve from there.

But Kennedy was having none of it, as outlined in his September 12, 1962 speech at Rice University:

We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of preeminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theater of war… But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win…

As for the U.S., as the initial glow of the accomplishment of putting a man on the moon rapidly wore off, and with public support almost nonexistent for further missions to the moon, it was deemed that taxpayer dollars would be much better spent for more down to Earth activities like spending approximately SEVEN TIMES the Apollo program’s entire cost sending older taxpayer’s children off to kill and be killed in Vietnam… a slightly less inspiring way to counter the communists. Thus, efforts towards the moon and beyond were mostly curtailed, with what limited funds were available for space activities largely shifted to the space shuttle program and more obviously practical missions closer to home, a move the Soviets quickly copied as well unfortunately.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why Didn’t the Apollo 13 Astronauts Just Put On Their Space Suits to Keep Warm?

- How Do Astronauts Go to the Bathroom in Space?

- How Do Astronauts Scratch an Itch When In Their Space Suits?

- NASA and Their Real Life Space DJ’s

Bonus Fact:

A little talked about facet of Kennedy’s goal for landing on the moon was actually to have the Soviets and the U.S. join together in the effort. As Kennedy would state in the aforementioned Rice speech, “I… say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours. There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful cooperation may never come again.”

Unfortunately, each time Kennedy proposed for the U.S. and Soviets join efforts towards this unifying goal, which seemingly would have seen the Cold War become a lot less hot, the Soviets declined. That said, for whatever it’s worth, according to Sergei Khrushchev, the son of then Soviet Premiere Nikita Khrushchev, while his father initial thought it unwise to allow the U.S. such intimate knowledge of their rocket technology, he supposedly eventually changed his mind and had decided to push for accepting Kennedy’s proposal. Said Sergei, “He thought that if the Americans wanted to get our technology and create defenses against it, they would do that anyway. Maybe we could get (technology) in the bargain that would be better for us…”

Sergei also claimed that his father also saw the benefit of better relations between the U.S. and the Soviet Union as a way to facilitate a massive cutback in military spending that was a huge drain on Soviet resources.

Sergei would further note that Kennedy’s assassination stopped plans to accept the offer, and the Johnson administration’s similar offer was rejected owing to Khrushchev not trusting or having the same respect for Johnson as he had developed for Kennedy.

Whatever the truth of that, thanks to declassified documents after the fall of the Soviet Union, we know that the Soviets were, in fact, originally not just planning to put a human on the moon, but also planning on building a base there as well. Called Zvezda, the planned Soviet moon installation was quite similar to the one outlined in Project Horizon, except instead of digging trenches, this base would simply be placed on the surface and then, if needs be, buried, but if not, the base was to be a large mobile platform to use to explore the moon.

Expand for References- Project Horizon

- Horizon V1

- Lunex

- LBJ’s Space Race: what we didn’t know then (part 1)

- Project Horizon

- Saturn A-1

- Claymore Mine

- Soldiers on the Moon?

- Exploring a Lunar Outpost

- Arthur Trudeau

- John Honeycutt Hinrichs

- Lunex- Another Way

- Zvezda

- Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

- Outer Space Treaty

- Space Policy

- Soviet’s Planned to Accept Kennedy’s Offer

- How Much Did the Vietnam War Cost?

- Cost of Major U.S. Wars

The post That Time the U.S. was Going to Build a Massive, Death Ray Equipped, Military Moon Base appeared first on Today I Found Out.

from Today I Found Out

by Daven Hiskey - May 30, 2019 at 01:59AM

Article provided by the producers of one of our Favorite YouTube Channels!

-

No comments:

Post a Comment